He's a Surreal Boy

Oneohtrix Point Never and the fresh allure of puppets

Oneohtrix Point Never

Regency Ballroom - San Francisco, CA

April 15, 2024

For as long as I’ve been in Oakland, the East Bay punk scene’s visual landscape has been saturated with the campy homespun look of puppetry, claymation, stop motion and cardboard menagerie. For the tenth consecutive year, John Waters will be hosting the Mosswood Meltdown festival, an annual gathering of new wave legends and garage rock standbys that is awash in the zany hues and off-color humor of the late great Paul Reubens. Depending on one’s preferred ratio of gleeful to grody, this Saturday morning cartoon kitsch informs everything from the nightmare fuel of Caroliner to the ‘60s girl group stomp of Shannon & the Clams.

Some of it works for me and a lot of it doesn’t–I always sort of chalked it up to a regional affectation akin to Austin indie rockers always wearing pearl snap shirts. It’s un-self-conscious low-brow fun, blissfully off-trend and more often interested in relishing rather than interrogating the manual forms of a bygone era. But over the last decade, as certain digital tools became more accessible, I always wondered if this kitsch would give way to something more forward-looking.

Then again, the most cutting edge visual effects are being applied to ends that appear no less shabby. Hollywood CGI, imposed on impractically shot green screen footage under crunch conditions, increasingly looks like ass. Alongside the abysmal stream of amateur crap littering social networks, the test ballooning of AI images in numerous high-profile promotional campaigns has primed even casual viewers to associate its composite visual grammar with all-too-human laziness. While the technology will no doubt improve, the hallucinations and broken text smoothing into passable legibility, the dominant read is that these sophisticated tools, especially in professional use cases, are intended not for the crucial symbiosis of play and innovation but lucrative corner cutting, the visual baby laxative for stepping on once-premier product.

More than a decade ago, Dan Lopatin of Oneohtrix Point Never betrayed an early unease about the rapidly-shifting terrain of sound design, characterizing electronic music production as an arms race. This was at the plateau of EDM’s dominance, the emerging dissonant pyrotechnics of deconstructed club, and the early days of SOPHIE’s formidable powers. Yet to come was the hyperpop bubble, all the big shiny promises of blockchain protocols, and AI finally hitting prime time.

Since then, Lopatin has scored two Safdie brothers films and served as musical director for The Weeknd’s Super Bowl halftime performance. A limited 2018 run of M.Y.R.I.A.D. shows, featuring his largest accompanying band and A/V arrangements to date, proved that he could go maximal if he wished. But his increased proximity to pop and prestige came as his OPN output turned inward: where his 2010s run of Age Of and Garden of Delete added the teen angst palette of nu-metal distortion and Reznor-fied vocal shredding to his already vast array of ambient and prog touchstones, his most recent albums (Magic OPN and last year’s Again) are explicit surveys of his past work–reexaminations of how his relationship to music has shifted, how his memories of past eras have unfurled today, and what he considers the numerous sonic paths not taken.

The San Francisco date of this tour was scheduled between the two weekends of Coachella, the American ur-festival where the main stage video screens were so mammoth they convincingly replicated the interior walls of a canyon. Having likely played a tough side stage slot the previous Saturday, Lopatin frequently took to the mic to express gratitude for the hyped SF audience’s whooping. “It’s really nice to play for an OPN crowd,” he admitted.

The impossibility of going toe-to-toe in the live space against the most highly-resourced artists and their attendant arsenals inevitably leads to thinking smaller. And so it followed, though I never would have predicted it, that the reigning king of sonic pastiche–an equal champion of the high and low, the contemporary and obsolete–took to the Regency Ballroom stage with a puppet show.

Mixing and jamming at his little battle station, Mini Dan was wearing a space age jumpsuit. His theater diorama, like the stage proper, was outfitted with fully operational lights and fog, captured with a mounted digicam and fed to the main screen behind the real man he was mirroring.

This was hardly the first time puppets have replicated in miniature the behaviors of an onstage performer to be broadcast on a larger backdrop. When touring The Information in 2006, Beck enlisted half a dozen technicians to handle a bopping foot-high avatar for each member of his live band. Though the Beck puppet mouthed the words pretty convincingly, it was mostly a cute, gimmicky whim on the lighter side of Michel Gondry.

Lopatin brought just one guy, the French designer and digital artist Freeka Tet, to operate Mini Dan and stage manage his technical flourishes. There were no strings attached: his head and hands were manipulated with big conspicuous metal rods. But the puppet’s imprecision, the clunkiness of its movements and the transparency of their source, did not break the spell. In fact, they fit impressively with Lopatin’s inquiry, and Gondry’s more intriguing commentary, on the nature of memory and dreams, where the most pertinent details are recalled in 4K while everything else dissolves in Gaussian blur. Mini Dan worked impressively as a stand-in for the guy who was too busy cuing tracks to emote, at times reading as a recollected past self, an abstract mascot of limited expression that nevertheless reflected something important about his original. At one point, Mini Dan lay crumpled under his equipment in despair.

That adorable gear setup was basically an aughts-era noise table (tiny Akai MPC 60, Line 6 green delay pedal, Boss loop station, presumably circuit-bent Casio SK-1), a nice Easter egg for the heads but also, I might argue, an intriguing bit of dream logic. Sorry for the dorm room bong sesh question but hear me out: have you ever actually looked at a screen in your dreams? I never have. The aperture of my dreams has never gotten that narrow despite so much waking life spent online–it must be too hard for my subconscious to generate such a sophisticated secondary interface. Same for any significant memories that have happened on digital devices; all the LiveJournal drama, legendary tweets, and momentous text or IM replies from crushes have smeared into concrete bits of information without a firm visual corollary. It leads me to think that when Lopatin dreams of performing or dips into his memories of being onstage, he’s likely tapping a sampler instead of staring into Ableton session view.

The show was hardly without cutting edge A/V techniques or the proven trappings of electronic music spectacle. Overlaid on the puppet feed were elaborate 3D-mapped objects and effect layers that stayed anchored even as Tet jostled the camera. The show’s first seismic kick drum, care of “World Outside”, gave a hearty subwoofer shove to the chest. Two fog machines spewed an immense vape cloud that crept across the room like a sandstorm before dissipating beautifully at the apex of “Ubiquity Road”. And when the puppet stage was darkened for Tet to reconfigure, the big screen delivered the rad video accompaniment one can expect from live OPN: late night VHS specters, a bleak loop of Fievel eternally lost at sea in An American Tail.

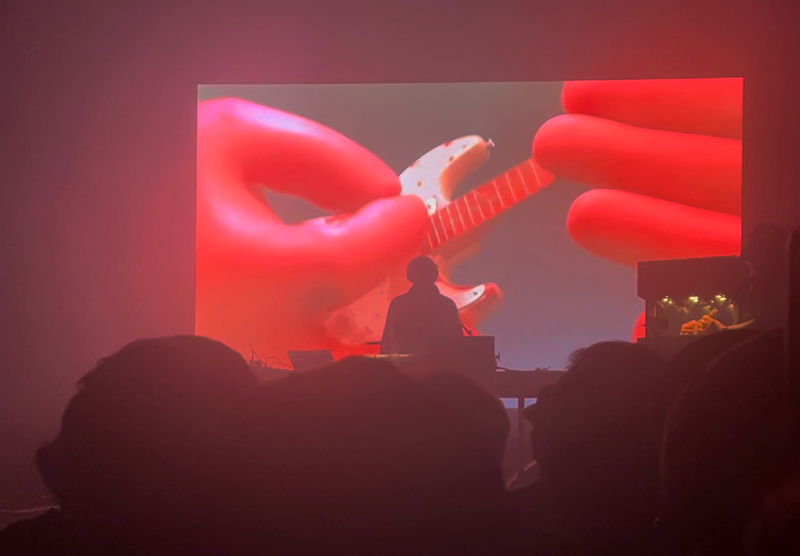

But OPN exploited the diorama concept to disorienting, fascinating effect. At times the entire room went dark except for the foggy puppet stage, glowing a menacing red. During “Krumville”, Mini Dan was set aside so Tet could put on a thick red pair of rubber gloves and pick up a detailed miniature Fender Telecaster. The song’s somber guitar breakdown, evoking Midwest emo or the calm before a Deftones storm, wasn’t recorded with a guitar. The dreary plucks are a signature bit of uncanny Lopatin sound design, earnestly tugging teenage heartstrings while wobbling with the too-clean precision of a physical modeling synth. It was thrilling to see that tension, a key node of the OPN project, out in the open: Tet’s Pixar-ed hands aped a picking posture, pantomiming playing guitar to a guitar track that sounded a whole lot like guitar but was definitively not.

I could not recall the last time I’d seen a show that, after bludgeoning me with a series of immense wide-angle gestures, directed my attention to so many tiny details. The ever-shifting scale was such an effective embodiment of OPN’s entire appeal: his swift moves from grainy ephemera to HD orchestration, from over-the-top piss take hyper-grunge to lonely tape hiss reverie. Leave it to the big font headliners to endlessly stack their armaments–for everyone else, the homespun and handheld present a more viable, intriguing way forward.

Revisiting the past always comes with pitfalls. As Sam Goldner argued in his review for Pitchfork, some of the signature moves on Again don’t so much re-contextualize as merely retread past triumphs. However, with Lopatin’s set list running deep into the back catalog, he thoughtfully re-worked fan favorites in a way that made good on the album’s central proposition.

The best of these was R Plus Seven’s immaculate “Boring Angel”. Whereas the original version slowly introduces and intensifies its Glass-ian arpeggios, Lopatin very quickly cycled through them to get to a completely different destination. The cathartic whorl grew unmoored in the stereo field, giving way to brand new synth leads that complicated their celestial beauty. As if expanding outward and away, these new harmonizations commanded the foreground as the arps floated off in a reverb expanse–the old version literally a distant memory.

I immediately thought of the first charming example of AI audio I ever heard: a series of expansions on the Microsoft start-up theme. Glutted with artifacts, these pieces take Brian Eno’s famous 3.5-second composition for a spin, at first encircling its familiar chime before stepping completely outside its bounds. It also reminded me of the least charming AI images to cross my timeline: those Adobe Generative Fill “expanded” versions of famous album covers that absolutely no one asked for.

I had to wonder: if you fed all those Eccojams tapes, Hudson Mohawke collabs and museum commissions into a neural network named Chuck Person, would it choose to iterate on “Boring Angel” this same way? I want to believe AI is not capable, the way Robert Rauschenberg was when he affectionately erased that de Kooning, of loving negation–it can’t see the past as a crucial part of oneself that nevertheless must be pushed aside.

At one point, the stage lights awoke to reveal that Mini Dan’s head had been replaced with a freaky visage; Tet reached into the shot to give him his real face back. The spell of the fourth wall is irreparably broken–it’s reassuring to see a human hand pulling the strings.