Beyond the Noise Table

Post-table practices from Flung, Lucy Liyou, and Briana Marela

Lucy Liyou, Flung @ Bottom of the Hill

San Francisco, CA

December 2, 2023

Briana Marela @ Bottom of the Hill

San Francisco, CA

November 13, 2023

Something occurred to me while I was enjoying a burbling 8pm set from San Francisco producer and vocalist Flung. There was bedroomy glitch, a bit of gamer sound grammar (woozy square-wave synths, hi-hats swung in skittery clusters), a wind chime dangling from a mic stand–Flung even ripped a genuinely soulful slide whistle solo. For a newish project that debuted with a cassette dropped during quarantine, it had the blooming energy of a multi-faceted project successfully striding from the DAW to the stage. “Somebody’s working on a thing / they’re dying to show you” she sang, telegraphing a labor of love being excitedly brought to light.

This kind of genre-indifferent solo electronic bricolage–like the idiosyncratic meshes of YYU or more eaze–is very much my shit, and I frankly love seeing it at this stage of development, where the tangle of inspirations has tightened into a durable presentation that still vibrates with the latent potential to move or scale in any direction. Flung’s modest gear array was only allotted an opener’s cramped footprint at the front of the stage, giving her occasional extroverted melody or overdriven beat a seam-bursting quality. Watching her exceed physical limitations, I recognized my excitement as that of catching an artist emerging from what could be deemed the “noise table” stage.

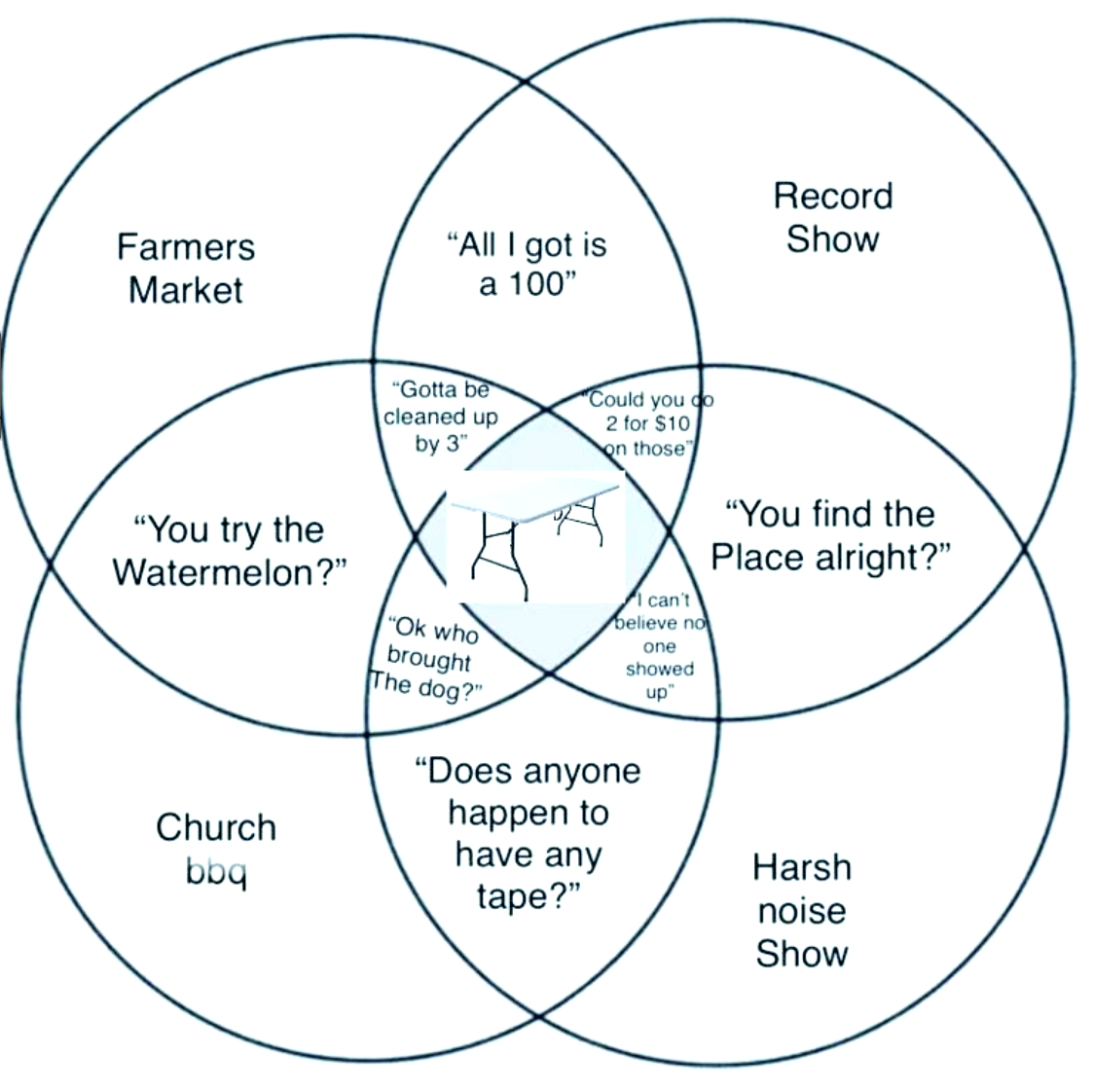

Often the only flat surface at hand in a bar or house venue, the metal folding table has become a standard blank canvas, the default stage plot for upstart hardware electronics performers from every corner. Though not at all relegated solely to noiseniks, that crew has so enthusiastically embraced the dingy furniture that it has come to bear their namesake. Almighty noise memelord Inzane Johnny, a.k.a. Wolf Eyes’ John Olsen, spent much of November ‘shopping white Costco tables into black metal sigils and classic freak jammer album covers. (Olsen sharing a dumb Chris Corsano meme I crafted during quarantine should give you an idea of how I was using my time.)

The noise table is certainly punk in its re-purposed church banquet banality, but it also exists somewhat uncomfortably between traditions. At a rap show, the DJ riser implies the presence of one or more MCs who will commandeer eyeballs in front of it. In the club, the mixing booth is a glorified production workstation, only nominally perceived as a traditional “performance” zone, if at all. The accepted precedent is that a person standing behind a table, their eyes downcast in concentration, is electing to physically diminish themselves in favor of the sounds they’re bringing forth (it follows that ambient, concrète, and computer music composers tend to take a seat). A more traditional vocalist, or anyone else trying to embody or project exuberance, appears cloistered.

That the tables are super ugly doesn’t help; worse, they’re an ergonomic nightmare. It pains me to see anyone taller than 5’ 6” awkwardly hunching over a sequencer or assuming unhealthy carpal posture to paw at a synth. Flung had wisely leveled up to the DIY maestro’s next rig of choice: a big ol’ wooden board of samplers and pedals balanced on a comfortably waist-high keyboard stand. Yet some refuse to be impeded by the noise table’s crude utility: Bay Area instrument maker Victoria Shen, whose EvicShen project includes playing doctored vinyl LPs on various self-built mods like acrylic nails embedded with stylus needles (an idea so good it was bipped for a Beyonce feature in British Vogue), is the first noise table jockey I’ve ever seen crowdsurf the fucking thing.

Having crossed the Rubicon, the noise table is less an object or practice and more a wide-reaching ethos. The canvas is large and can bear a lot of weight. Last month I saw two more Bay Area electronic artists, of practices noisy and not, set the table to the side so as to better harness its bounty.

Lucy Liyou showed just how many modes it can carry. Her recordings include soft-as-a-pin-drop sound collage, vulnerable family narratives read with text-to-speech vocalizers, and breathy R&B melodies over ambient piano atmospheres. At turns her set involved all of these, but also fully hi-res ballads, campy Disney strings, and industrial noise in service of a tightly-synched, bombastic melodrama. With moments of pensiveness, grief, despair and hilarity, it was as if Mariah Carey, Sun Ra and Jaime Stewart scored a bodice-ripping queer telenovela.

Whether there was an explicit narrative or not, Liyou managed to unite the set's many disparate affects: mourning, exaltation, dada horniness ("take off my sub-scarf"), desire (fatuous), desire (thwarted), jealousy, agony. One might assume placing a song about painful loss next to a bugged-out anti-patriarchal retooling of “Old McDonald Had a Farm” would scramble the sincerity, but Liyou’s total commitment and execution made room for all of it. Through the hairpin dynamic turns, Liyou’s every movement or facial expression was in service of its plot beats or luxurious asides toward an arresting, continually rewarding muchness.

To her left was a table propping up a computer, the source of the elaborate backing tracks and cast of voices she conversed with, as well as a spread of goodies: a can of Spam, an otomatone. Directly in front of her was a weighted electric piano. Unencumbered, Liyou rarely averted her forward gaze, leaning over the board to preen and mean-mug, managing complex melodic figures while throwing side-eye.

In fact, the piano was rarely used for traditional chordal accompaniment, rather to take broad, sonorous leads or provide rapid filigree of many stunning forms. Liyou’s flawless multi-octave arpeggios made evident her classical training, but she also bashed the keys with the heel of her palm, shot atonal death-stare chords, and enlisted the Spam for glissando. The piano as instrument was an interlocutor of its own and, as foregrounded object, served as a dais for Liyou’s direct address or sung yearnings. The set concluded with a long and rapturous solo, a totally dazzling collapse of exacting technical proficiency, trollish cacophony, and heart-bearing determination. Yes, we all contain multitudes, but Liyou unflinchingly bears hers in a brilliant whole.

In a more spacious mode, Briana Marela used a table full of electronics, also situated stage left, in support of her lyric-driven experimental pop. A graduate of the heralded and tragically defunct music graduate program at Mills College, Marela uses sophisticated light, motion, and touch inputs to alter a complex array of Max/MSP patches, software and vocal effects. Like Liyou, Marela’s performance involved an element of theater: her poised, deliberate gestures and object manipulations activated, quelled, or modulated her lush digital tones.

Here, nothing was mere furniture. In fact, the height of a table delineated yet another expressive plane: when Marela raised her hands, chords instantly awakened or more vibrantly shimmered; when she dropped them to her side, the sounds were dimmed or terminated. These corresponding moves, and the dreamy synth beds that suspended time, felt pretty magical–she even had a black velvet stand at center stage where the lights, bowls, and other activated objects of each composition were placed. But any flourishes or tech illusions only served to reinforce Marela’s serene, at times heavy self-examination.

Having released several albums of electronic indie pop, Marela brings a melodic sensibility to the often fragmented world of abstract synthesis. Singing into a headset mic, her voice was the signal upon which most of the pieces were built, constantly expanding, dilating, or partnering with vocoded tones. Instead of linear song structures, the pieces ebbed in a considered, conversational lilt. Often, an elongated lyric–and its encircling wave of anticipation, dread, reverie or fallout–was a discrete event given plenty of space to breathe, to take honest account.

Some of these were concerned with love, its absence or conditions, others the embattled sides of the self. Holding a mirror to her face, the object (its light reflections? I was too awed to decide) introduced a second voice to her melodies, matching her bright soprano with an unstable and disgruntled baritone. Laurie Anderson has famously down-shifted her own speech into a trademark blowhard known as “the voice of authority”; Marela’s was the voice of doubt, of self-critical discouragement, the wretched harmonization that haunts our intentions.

There were also moments of uncomplicated wonder. At one point she displayed a kind of bespoke garden box with several ornate metal blooms. Plucking one out, the contact completed a circuit that spun the twinkling arpeggios faster. “I’ve never smelled this flower before,” she said, and I certainly hadn't either.

Despite these artists' pedigree, vulnerability doesn’t require any special training or equipment. The noise table is still a reliable site for transcending the prosaic, for exploring extremes and uncertain outcomes. But if the effort feels in any way confined, one should, one way or another, get the table out of the way.